Part Five

Vienna

Part Five

Vienna

Part Five Vienna

November 18, 1908: Police records show that Hitler takes up new lodgings on the Felberstrasse (Room 16/22) on this day, listing himself as a student.1 He now lives alone in Vienna, with no known friends or gainful employment; subsisting upon whatever savings he has remaining, to supplement his small orphan’s pension. Unfortunately, because there are no completely reliable witnesses as to Hitler's habits and activities during this period, it is a matter of speculation as to what they were. However, since his income is so meager, and he will only manage to maintain these quarters for a mere 9 months, it can be safely assumed that his activities are limited. It is likely that his main pursuit is a continuation of his solitary studies, based on books at the two Viennese lending-libraries, to which he is known to have been a subscriber.2

March 4, 1909: Hitler cancels his membership to the Museum Association in Linz. He probably takes this step because he can no longer afford to keep up his annual dues of 8.40 Kronen.3

In Mein Kampf, Hitler will claim that his Vienna years were when his political philosophy was formed, testifying that by the time he left Vienna he had learned all he needed to know concerning the Jews. There is absolutely no evidence for this contention. On the contrary, there is much testimony that many of Hitler’s acquaintances during these years were Jews. There are no reliable accounts whatsoever that would give even a hint that he was in any way anti-Semitic at this time.4 However, Hitler did formulate views on certain issues that would stay with him in later years, especially his aversion to the Social Democrats, and parliamentary politics in general. With the intention of maintaining a biographical focus, the evolution of Hitler’s political worldview will be confined to those aspects obviously germane to his time in Vienna.

Adolf Hitler, from Mein Kampf:

At all events, these occasions slowly made me acquainted with the man and the movement, which in those days guided Vienna’s destiny: Dr. Karl Lueger I, and the Christian Social Party. When I arrived in Vienna, I was hostile to both of them. The man and the movement seemed ’reactionary’ in my eyes. My common sense of justice, however, forced me to change this judgment in proportion as I had occasion to become acquainted with the man and his work; and slowly my fair judgment turned to unconcealed admiration. Today, more than ever, I regard this man as the greatest German mayor of all times. How many of my basic principles were upset by this change in my attitude toward the Christian Social movement!

From The History of Anti-Semitism by Leon Poliakov:

It soon became apparent that, especially in Vienna, any political group that wanted to appeal to the artisans had no chance of success, without an anti-Semitic platform . . . . It was at that time that a well-known phrase was coined in Vienna: "Anti-Semitism is the socialism of fools." The situation was exploited by the Catholic politician Karl Lueger, the leader of the Austrian Christian-Social party, with a program identical to that of the Berlin party of the same name, led by Pastor Stoeker. In 1887, Lueger raised the banner of anti-Semitism . . . . However, the enthusiastic tribute that Hitler paid him in Mein Kampf does not seem justified, for the Jews did not suffer under his administration.

Lueger was opposed by the Austrian Kaiser himself, and Lueger’s political skill at playing every conceivable card, including the Rabbi of Spades, filled Hitler with an admiration that would drive him, in later years, to emulate the mighty mayor. It seems likely that a greater share of this admiration was due to the practical results achieved by this unique form of populist anti-Semitism. Historian William L. Shirer will write that Lueger’s "opponents, including the Jews, readily conceded that he was at heart a decent, chivalrous, generous, and tolerant man. So there is not a lot of evidence to support his large effect on the views of Adolf Hitler."

The population of Vienna at this time is 2, 031, 420, with 175,294 Jews. Thus the Jewish population is a mere 8.75% of residents overall. Many of these are recent arrivals and not registered to vote, making them a perfect segment of the populace upon which to score political points through populist utilization of existing prejudice.

In his book The Pity of It All: A Portrait of the German-Jewish Epoch, Amos Elon writes that "Lueger’s anti-Semitism was of a homespun, flexible variety--one might almost say gemuetlich [having a feeling or atmosphere of warmth and friendliness]. Asked to explain the fact that many of his friends were Jews, Lueger famously replied: ’I decide who is a Jew.’"

It is accepted, by even the dullest of biographers, that the mayor was a major role model for Hitler’s Führer, practically a prototype. To be fair, Hitler perfected the model, and brought it to a point that probably would have shocked—if not completely horrified—the man who was its earliest inspiration.

August 20, 1909: Hitler abandons his apartment on the Felberstrasse, and moves into less expensive accommodation at 58 Sechshauserstrasse. The move is probably strictly one of economy, as it is likely that his small savings have been now been exhausted, or will soon be.5

August 22, 1909: As is required by law, Hitler registers his change-of-residence with the local police. He puts down "writer" in the space for occupation.6

Autumn 1909: Hitler fails to register for military service as required by law. Had he registered, he would have been ordered to report after his twenty-first birthday, which is on April 20, 1910. He will later claim that he does this, in order to avoid serving in the army of a state he detests.7

September 16, 1909: After less than a month at 58 Sechshauserstrasse, Hitler moves out, under unknown circumstances. Contravening the law, he fails to file the proper change-of-residence forms with the local police. His savings are now probably long gone and, while he is still receiving his small orphan’s pension, it can be assumed that it is not enough to maintain both lodgings and food. He now undergoes a period of homelessness, presumably spending his nights on park benches or other accessible areas.8

Click to Enlarge

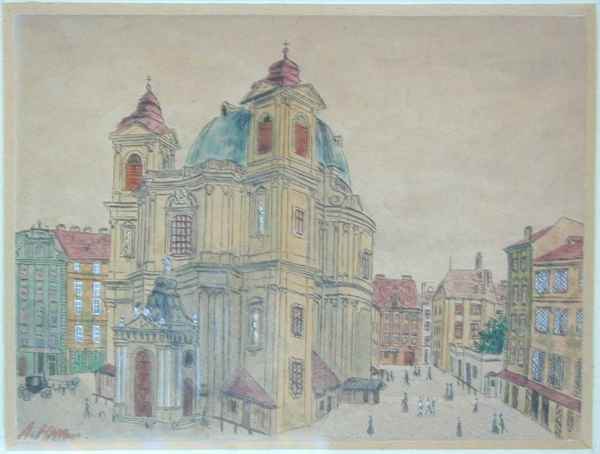

Hitler: St. Peter’s Church, Vienna

While there are many charitable organizations active in Vienna, they are not enough to meet the needs of all of the city’s homeless. There are long lines at the Waermestuben (warming-up rooms), shelters, and soup kitchens; and many are regularly turned away. Hitler now turns to these resources as he struggles to stay warm, and feed himself, amidst the downtrodden masses. Near his first apartment in Vienna is the Hospital of the Sisters of Mercy, where free soup is distributed. One of the relatives of his former landlady, Frau Zakreys, testified to seeing him there, "standing in the cloister’s soup line; his clothes looked very shabby, and I felt sorry for him, because he used to be so well dressed."9

Viennese social-affairs reporter and author, Ernst Klaeger, described one of the Waermestuben in the Brigittenau district:

We now stumbled through a dark gate, entering a large, and only dimly lit room, where long benches, on which people were squeezed together, were put up in all directions. The sight of these people, sitting in long crammed lines, so that there was no room to move even slightly, caused us physical pain, and we hardly felt it when the warden used his elbows to make enough room for us to force ourselves into the long line of pent-up people . . . . We sat in this painful position for hours . . . . Yet, around us, there was dead silence. As if under a spell, people remained motionless within the quadrangle of the benches, looking like a ghastly gallery of the dead, whom someone had had put one next to the other, as if for some horrible amusement . . . . Welfare institutions are society’s failed attempts to rid itself of its guilty conscience. They appeared to me like a bad dream image, those vast crowds of believers who wait out there in the barren darkness, outside the bright gates of our rich life, utterly blinded by its external beauty. One must have seen them the way I saw them: suppliant, with greedy eyes; threatening, and foaming with rage in their powerlessness, thousands and thousands of society’s enemies, raised by our mercy.10

December 1909: With the onset of the cold of winter, 20-year-old Adolf Hitler takes up residence at Vienna’s Asylum for the Homeless (Asyl fuer Obdachlose) in Meidling, near the Schoenbrunn Palace. The hostel, known as the Meidlingen, while very overcrowded, provides an evening meal of soup and bread, a bath, disinfection of clothing; and dormitory lodging for the night. However, the shelter only provides for short-term stays and, in addition, the residents are not allowed to stay inside during the daylight hours, but are forced to spend their days on the streets after 9:00 AM, presumably seeking employment.11

It is during this time that Hitler meets a petty thief and fellow resident of the hostel, Reinhold Hanisch. It is through Hanisch that most of what we know of Hitler during this period originates. While his account is hardly beyond suspicion in many of its details, nevertheless, it is beyond dispute that he actually knew Hitler, and therefore his testimony is invaluable, if utilized with prudent caution. Hanisch, a Bohemian who is a native of the Sudetenland, living under the assumed name Fritz Walter, befriends the down-and-out would-be artist. He teaches him the ropes of shelter existence, taking him along, after the doors of the charitable establishment are locked in the morning, to a convent near the Gumpendorferstrasse, to receive soup, provided by the nuns. Hanisch relates that his attempts to motivate Hitler to earn money through labor—such as shoveling snow—fail, due to Adolf’s natural indolence, and his weakened, undernourished, and ill-clad state.12

Hitler: Untitled WatercolorSometime around Christmas, Hitler receives a gift of 40 Kronen, presumably from his Aunt Johanna. He uses this gift to purchase a warm coat from a state-run pawnshop, and some art supplies. Hitler uses these materials to embark on a period as a street artist, painting pictures of landscapes and Vienna landmarks, to sell to tourists and local dealers. Hanisch will claim that the idea for this enterprise was his own, and he had to talk Hitler into it, and this is probably accurate enough. He also relates that Hitler had told him that he had actually been a student at the Academy. In any event, it is Hanisch who, for a cut of the proceeds, peddles Hitler’s finished paintings to prospective buyers--usually post-card sized scenes copied from photographs--leaving the young artist free to paint.13

Adolf Hitler, from Mein Kampf:

In the years 1909—10 I had so far improved my position that I no longer had to earn my daily bread as a manual laborer. I was now working independently, as draftsman, and painter in watercolors. This metier was a poor one indeed, as far as earnings were concerned; for these were only sufficient to meet the bare exigencies of life. Yet it had an interest for me, in view of the profession to which I aspired.

February 9, 1910: Since the hostel at Meidling only allows for temporary residence, Hitler is forced to find more permanent lodgings. He succeeds in securing quarters at the Mannerheim, a home for single men, for 50 Heller a night. The Mannerheim, partially funded by charitable donations--including the Rothschild family--allows a little more privacy to the residents, and Hitler acquires his own cubicle. There are also laundry facilities, a canteen, a library and reading room, and even a ’workroom.’ Hitler becomes a regular in the workroom, joining a small group known as the ’intellectuals.’ Unlike the majority of the residents, the members of this group don’t leave the Mannerheim to do manual labor during the day, but inhabit the work room, writing or, like Hitler, painting or drawing.14

April 3, 1910: Almost two months after Hitler moves from the Meidlingen shelter, a riot breaks out, when 200 people, trying to gain shelter there, are turned away. Police have to use force, to stop the crowd from storming the gates and taking the place over. The local newspaper, the Arbeiterzeitung, writes:

Thus Vienna’s disgrace has been made permanent, the disgrace of rich Vienna where, night after night, hundreds of people are forced to crawl into miserable caves; and we cannot offer them shelter, but only police sabers instead.15

Click to Enlarge

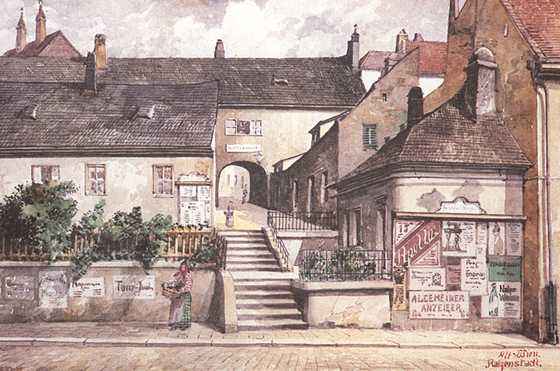

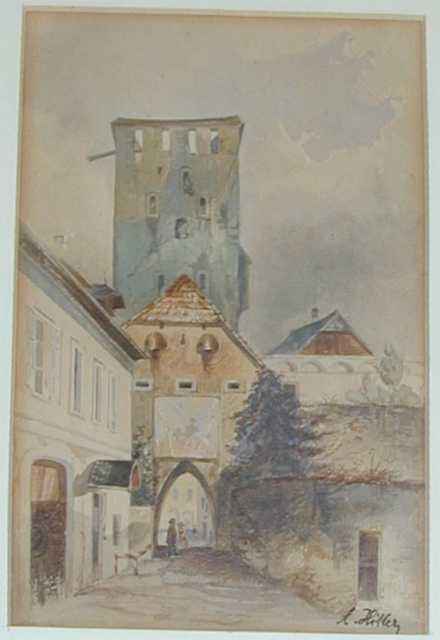

Hitler: Lamberg Castle

April 1910: Hitler receives a commission from upholsterer Karl Pichle, who operates a shop at 30 Hernalser Haupstrasse in the Hermals district. He is paid to paint a spring and fall landscape, and is soon painting full time. He receives commissions from a glazier, Samuel Morgenstein, and proceeds to create many pieces a little more ambitious than the postcard-size works he initially produced. He soon discovers an additional market for watercolors: to be used by picture frame manufacturers, to display their finished frames. On average, he receives only 3 - 5 kronen per painting. The daughter of one of these frame manufacturers, Jakob Altenberg, would later complain that Hitler’s paintings were of poor quality:

These were the cheapest items we ever sold. The only ones who showed any interest in them were tourists, looking for inexpensive souvenirs.16

Click to Enlarge

Hitler: The Werder Gate

June 21, 1910: Hanisch later testified that, at this time, Hitler receives 20 Kronen, his half-share of a large sale of paintings. His story is seemingly confirmed by the hostel records, which indicate that, on this day, he gives notice that he intends to move. He then disappears for a week, to an unknown location.17

Hitler: Karlskirche (St. Charles’s Church), Vienna

June 26, 1910: Hitler returns, and registers again at the hotel, after having apparently gone through the entire 20 Kronen windfall.18

Late July 1910: When Hanisch fails to return with the proceeds for two of Hitler’s paintings he was supposed to sell, Hitler files a complaint with the local police, in an attempt to recover these funds.19

Hitler: Town of the Mice, Vienna

August 1910: Siegfried Loeffner, a Jewish postcard salesman, who often sold pieces for Hitler, spots Hanisch on the street and confronts him about his misappropriation of Hitler’s paintings. When the two argue loudly and begin to scuffle, a policeman intercedes. Learning the nature of the dispute, and discovering that Hanisch does not carry the proper identification, he hauls the both of them off to the district police commissariat of Weiden. For some reason Loeffner claims that he does not know Hitler personally, when of course he does, and swears out a formal statement to the police:

Siegfried Loeffner, agent, XXth District, 27 Meldemannstrasse, states: I learned from a painter at the men’s hotel that the arrested man sold pictures for him, and had misappropriated the money. I do not know the name of the painter, I only know him from the men’s hotel, where he and the arrested man always used to sit next to each other.20

August 5, 1910: Hitler’s complaint against Hanisch goes to trial, and he swears out a statement for the court.21

From Court records:

Adolf Hitler, artist, born 20.4.1889 in Braunau, domiciled in Linz, Catholic, single, now living at 27 Meldemannstrasse, XX District, declares: It is not correct to say that I advised Hanisch to take the name of Walter Fritz. I have never known him by any name except Walter Fritz. As he was without means, I gave him the pictures I painted, so that he could sell them. He regularly received from me 50% of the sums realized. For roughly two weeks, Hanisch has not returned to the Mannerheim; and has defrauded me of the Parliament painting, worth 50 Kronen; and a watercolor, to the value of 9 Kronen. The only document belonging to him that I have seen is the said employment book, in the name of Fritz Walter. I have known Hanisch from the time I lived at the Asylum in Meidling. Adolf Hitler. August 5, 1910.22

August 11, 1910: Hanisch is convicted, but only of using an assumed name. He had claimed in court that he had sold the Parliament painting for 12 Kronen, and given Hitler his half; but Hitler denies he had received any payment. Hanisch will later admit that he had sold the painting to a frame-maker, Wenzel Rainer. He gives the reason that he could not reveal this information to the court, because Rainer had given him another commission meant for Hitler, which he had fulfilled himself, and he didn’t want to have his double-dealing exposed. Hanisch is sentenced to one week in jail. Hitler never does recover what he believes he has been cheated out of.23

Another political aspect of Hitler’s worldview that he claimed was formed at this time—and on this issue we may safely assume that he is speaking accurately—is his life-long aversion to parliament. Not only did Hitler paint pictures of the Viennese parliament, he writes of observing the Reichsrat (above, not by Hitler) from the gallery, something Kubizek confirms. Hitler tells us that, before attending sessions of Vienna’s version of parliament, the Reichsrat (Imperial Council), he was well disposed to the institution. In fact, he asserts that he was "one who cherished ideals of political freedom" and "could not even imagine any other form of government." He goes on to claim that, in light of his "attitude towards the House of Habsburg I should then have considered it a crime against liberty and reason to think of any kind of dictatorship as a possible form of government."

He then quickly moves to argue that the "parliamentary principle of government by numerical majority necessarily leads to the destruction of the principle of leadership," because there is no one to whom to lay the responsibility for failure. He asks the rhetorical question: "can we say that the responsibility is fully discharged when a new coalition is formed or parliament dissolved?" This sort of fudging of responsibility, Hitler opines, "contradicts the aristocratic principle, which is a fundamental law of nature." His conclusion: "There is no other principle that turns out to be quite so ill conceived as the parliamentary principle, if we examine it objectively."

Hitler’s critique then moves on to the power of the Press: "Whatever definition we may give of the term ’public opinion’, only a very small part of it originates from personal experience or individual insight. The greater portion of it results from the manner in which public matters have been presented to the people, through an overwhelmingly impressive and persistent system of ’information’." He makes the further point that the Press, being "controlled" by Jews, is an evil force and cannot be relied upon to educate the people, but merely to propagandize them. Therefore, since public opinion is as worthless as the representatives of the people sitting in the Reichsrat, a new version of ’democracy’ is called for.

Adolf Hitler, from Mein Kampf:

As a contrast to this kind of democracy, we have the German democracy, which is a true democracy, for here the leader is freely chosen. and is obliged to accept full responsibility for all his actions and omissions. The problems to be dealt with are not put to the vote of the majority; but they are decided upon by the individual, and as a guarantee of responsibility for those decisions, he pledges all he has in the world, and even his life.

The objection may be raised here that, under such conditions, it would be very difficult to find a man who would be ready to devote himself to so fateful a task. The answer to that objection is as follows: We thank God that the inner spirit of our German democracy will, of itself, prevent the chance careerist—who may be intellectually worthless and a moral twister—from coming, by devious ways, to a position in which he may govern his fellow-citizens. The fear of undertaking such far-reaching responsibilities, under German democracy, will scare off the ignorant and the feckless.

But should it happen that such a person might creep in surreptitiously, it will be easy enough to identify him, and apostrophize him ruthlessly: "Be off, you scoundrel! Don’t soil these steps with your feet; because these are the steps that lead to the portals of the Pantheon of History, and they are not meant for place-hunters, but for men of noble character." Such were the views I formed, after two years of attendance at the sessions of the Viennese Parliament. Then, I went there no more.

While it is doubtful that Hitler’s thoughts on this subject were quite as complete in Vienna as this passage claims, this is in fact an early formulation of what would come to be known as the Fuehrer Principle (Führerprinzip).

Click to Enlarge

Hitler: Castle Battlements, 1910

December 1, 1910: Bank records indicate that Hitler’s Aunt Johanna withdraws her 3,800 Kronen life savings. While there has been much speculation that Hitler received a large share of these funds, as an inheritance, no direct proof of this has ever been found. The large sum he had received previously from his aunt (1907), to finance his stay in Vienna, probably equaled his rightful share, in any case. In the event, his present lifestyle remains unchanged, and he continues to produce his paintings as usual.24

March 21, 1911: Hitler’s aunt, Johanna Poelzl, dies. Hitler’s half-sister, Angela, who is providing for his full-sister Paula, as well as her own three children, files a claim for the remains of Aunt Johanna’s estate, noting that Hitler had previously received the large sum of 924 Kronen from her in 1907, to fund his ’studies’ in Vienna.25

Hitler: Door of the Scots, Vienna, 1911

May 4, 1911: Hitler is ordered to surrender his 25 Kronen-per-month orphan’s pension, to his sister, Paula.26 From court records:

Adolf Hitler, now living as an artist at 27 Meldemannstrasse, XX District, has testified as follows in the court of Leopoldstadt: He is able to maintain himself, and agrees to the transfer of the full amount of his orphan’s pension to his sister and, in addition, inquiries have revealed that Adolf is in possession of considerable sums of money given to him by his Aunt Johanna Poelzl, for the purpose of advancing his career as an artist.27

September 17, 1911: On a Sunday morning, thousands of Viennese workers take to the streets, to protest price increases for meat. The crowd marches through the city and converges on the Viennese City Hall, where the police, three divisions of cavalry, and seven battalions of infantry are waiting for them. These troops cordon off all access roads to the Hofburg, to protect the emperor, as over 100 protesters are arrested in the ensuing scuffle. Three workers die. While Hitler gives no date in the following passage from Mein Kampf, it is very likely that it is this very demonstration he is writing about:

I pondered with anxious concern on the masses of those no longer belonging to their people, and saw them swelling to the proportions of a menacing army . . . . For nearly two hours, I stood there, watching with bated breath, the gigantic human dragon slowly winding by.

The Illustrierte Kronen-Zeitung writes of the protest:

In every street through which the demonstrators passed, there were serious clashes, and the crowd’s violent anger reached its climax when a squad of hussars approached on horseback. Shouts were heard: "Now they're letting the Hungarians loose on the Viennese!" And then, when the Bosniaks advanced, there were piercing whistles, rocks were thrown, and people shouted, "The Bosniaks have no business here!" From that point on the rally threatened to turn into a revolution, comparable only to the one in 1848.28

March 22, 1912: Hitler walks across town to the Sofie Halls in the Third District, to attend a lecture by his favorite author, Karl May. May is an ex-convict and avowed pacifist from Saxony who had authored numerous popular adventure stories set in the American Wild West, while never personally setting foot outside the continent of Europe. Hitler had read all of his many works, and would continue to read and admire May until his final days.

May is at this time steeped in controversy. A story had recently been published that he had spent time in prison as a young man, for fraud and theft. Hitler defends May to the other boarders at the hostel, saying that using his past against him is unfair, and that those who would do so are hyenas and scoundrels. Three thousand people attend the sold-out lecture, the title of which is "Up into the World of the Noble Man."29

From local newspaper coverage of May’s lecture:

What was particularly interesting was the lecture evening’s audience. Petit bourgeois and suburban women and men, small white-collar workers, adolescents of both sexes, and even boys. Every one of them is bound to have a subscription to a public lending library, and to have read all sixty volumes of Karl Mays works: the fantastic travel stories and novels, whose authenticity has been doubted so often, and which have been the object of long, bitter legal suits . . . .

May is a seventy-year-old gentleman; a gaunt, old-fashioned figure, with a half-bureaucratic and half-pedagogical head, which is surrounded by short white curls. He alternately puts a pince-nez made of horn, or glasses in front of his cheerful eyes . . . .

May explains his Weltanschauung [worldview] in a rather unstructured and erratic manner. He says he has always striven upward, toward a freer, spiritual world of noblepeople. He alternately calls himself a soul, a drop of water, and--his favorite--a mental-spiritual aviator, and, now and then, reaches under the table for one of the numerous volumes of his collected works, to read more or less philosophical observations, fairy tales, parables, and poems. The strangest thing about what he says is his seriousness, his bathetic and genuine enthusiasm, which has something of a religious kind of enthusiasm about it.30

March 30, 1912: Just one week after Hitler attends his last lecture, Karl May dies of "paralysis of the heart, acute bronchitis, asthma" and what is probably undiagnosed lung cancer. Hitler is reported to have been "deeply upset" by his death and was "genuinely very sorry about it."31

Click to Enlarge

Hitler: Vienna Opera House Figure Study in red pencil

Early 1913: It is around this time that one of the more reliable witnesses to Hitler’s last months in Vienna makes his appearance. Karl Honisch (not to be confused with Reinhold Hanisch), of Czech origin, encounters a Hitler at home among the ’intellectuals’ in Mannerheim’s workroom. He notes that Hitler had his own recognized space in the workroom. If someone tried to take this place, they would be warned by one of the others: "This place is occupied. This is Herr Hitler's place!"

Honisch will later write that Hitler was one of the main members of the ’intellectuals,’ and that "he used to sit in his place day by day with almost no exception and was only absent for a short time when he delivered his work; because of his peculiar personality. Hitler was, on the whole, a friendly and charming person, who took an interest in the fate of every companion . . . . Hitler was not an average person like us and, despite his 24 years, mentally he was superior to all of us . . . . Nobody allowed himself to take liberties with Hitler. But Hitler was not proud or arrogant; on the contrary, he was goodhearted and helpful."32

Honisch relates that Hitler was always willing to engage in conversation with his fellow residents:Thus I remember a thirty-year-old man by the name of Schoen. He was an unemployed estate manager, who apparently had a degree from a technical university. Hitler and he would frequently discuss agrarian issues, and Hitler took this so seriously that he would often take up pencil and paper to take notes. Then there was a certain Mr. Redlich, who had a graduate degree . . . . And there were several others, whose names I don’t recall, among them workers and craftsmen, from whom Hitler was eager to learn about their professional fields.

The Mr. Redlich mentioned by Honisch will later be identified as civil servant Rudolf Redlich, a Jew from Moravia, who resided at the Mannerheim from December 30, 1911 to June 28, 1914. This is yet another confirmation that Hitler, during his Vienna years, never showed any particular aversion to Jews. In fact, many of his Mannerheim peers were Jews, as were many of the local art dealers to whom he sold his paintings. From this and other accounts, it is clear that Hitler’s later testimony—claiming that it was his time in Vienna that "opened his eyes" to the "insidious nature of the Jews"—is a total fabrication. It would not be until after WW1 that Hitler would display any anti-Semitism whatsoever.33

February 4, 1913: Nineteen-year-old shop assistant Rudolf Haeusler, originally from Aspang in Lower Austria, takes up residence at the Mannerheim. Four years his junior, Haeusler and Hitler, who both enjoy painting, become fast friends and refer to each other as ’Rudi’ and ’Adi’.34

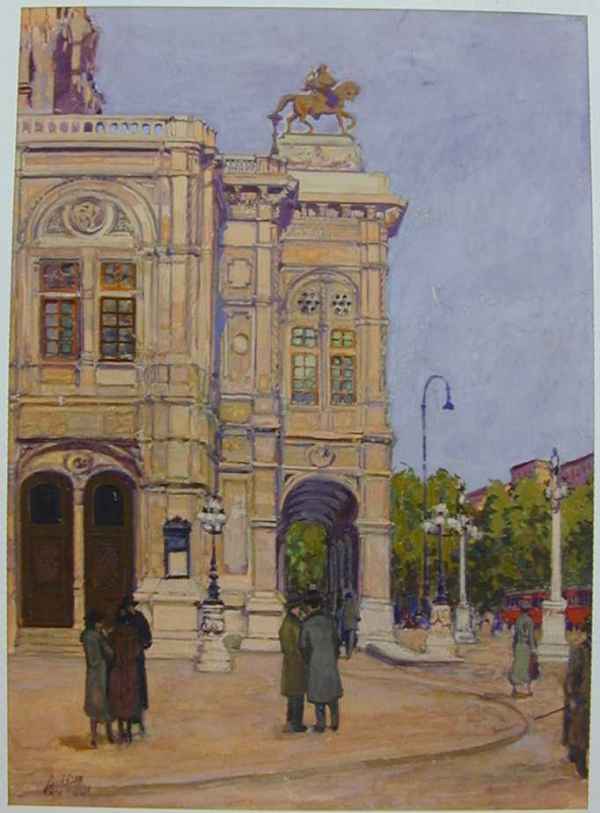

Hitler: Vienna Opera House

April 20, 1913: Hitler celebrates his twenty-fourth birthday. He is now eligible to collect his inheritance from his father, which he immediately applies for.35

Vienna Opera House

May 5, 1913: Hitler and Haeusler attend a Mahler-Roller production of Wagner’s opera, Tristan and Isolde, in the standing room only section of the Vienna Opera House.36

May 16, 1913: The District Court in Linz approves Hitler’s application for his inheritance, which, with interest, totals the substantial sum of over 819 Kronen.37

Hitler: Old City Gate, Deutsche-Altenburg, Austria

May 24, 1913: After purchasing a full wardrobe of new clothes, and with his sizable inheritance in his pocket, Hitler moves from Vienna to Munich, in Bavaria, accompanied by Rudolf Haeusler. For the first time since setting out on his own, Adolf Hitler takes up residence in Germany proper.38

End of Part Five.

Next: Munich.

Written by Walther Johann von Löpp Copyright © 2011-2016 All Rights Reserved Edited by Levi Bookin — Copy Editor European History and Jewish Studies

Twitter: @3rdReichStudies

Disclaimer: The Propagander!™ includes diverse and controversial materials--such as excerpts from the writings of racists and anti-Semites--so that its readers can learn the nature and extent of hate and anti-Semitic discourse. It is our sincere belief that only the informed citizen can prevail over the ignorance of Racialist "thought." Far from approving these writings, The Propagander!™ condemns racism in all of its forms and manifestations.

Fair Use Notice: The Propagander!™may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of historical, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, environmental, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a "fair use" of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.