The Italians were frustrated by the Munich summit. Mussolini said: "Germany can be compared to a very lucky gambler who has always won as he doubles his bets. Now he's a bit nervous and wants to take his winnings home. In truth, Hitler wants to negotiate with England, with whom he never wanted to go to war." Hitler told Ribbentrop privately: "I do not wish to have the antipathies between Italy and France influence any of our negotiations."

And Ciano wrote: "From everything Hitler is saying his desire to close all the issues quickly is obvious . . . He speaks with such moderation and insight that appear truly surprising after such a heady victory. I cannot be suspected of having excessive tenderness toward him, but today I truly admire him. Mussolini is visibly embarrassed. He feels that he is playing second fiddle. He relates the discussion with Hitler to me without hiding any bitterness or irony, and he concludes by saying that the German people already have the seeds of their own collapse, because a tremendous clash will take place that will blow everything away. What the Duce really fears is that the hour of peace is at hand and his lifelong dream will once again elude him: glory on the battlefield."

General Roatta: "Ciano was convinced that Germany feels like a poker player with too many chips. Isn't it better to step away from the table?"

General Pricolo: "The people surrounding Mussolini at Munich made the wrong decisions. General Roatta became the most prominent member because of his experience at international meetings and his perfect German. And immediately all questions discussed with the Germans were geared to territory and ground troops, while it was clear that the occupation of this or that part of metropolitan France was of secondary importance. It was obvious that with the fall of France, the war was to continue in the Mediterranean, in Libya, and East Africa. Due to Roatta's importance, the chiefs of staff of the three branches were basically cut off from the discussions. Everything was decided by Mussolini, Ciano, and Roatta with help now and then from Badoglio. General Perino told me that, at Munich, Hitler clearly proposed that Italy would have formulated, as armistice conditions, the occupation of French territory (up to the Rhone), as well as Tunisia and Djibuti."

Before leaving Munich, Mussolini, unhappy in his sidekick role to the victorious Fuehrer, gave General Perino the order to continue air force operations against the French bases. During the return trip, Mussolini called General Roatta to his railroad car and told him, with many omissions and withholding some points, what he had discussed in private with Hitler. To show his power, Mussolini confirmed that he would demand from France, Nice and its surrounding territory, Savoy, Corsica, Tunisia, Algeria, Djibuti, British Somaliland, a corridor to link Libya and Ethiopia, and the neutralization of both sides of the Straits of Gibraltar. Finally, not having consulted the interested parties, he will demand that the Egyptians substitute the alliance treaty tying them to England with a friendship treaty with Italy. Roatta reminded the Duce that as they were leaving, Keitel repeated his promise to support the projected Italian advance into France. While the Duce suffered from the position of inferiority he saw himself relegated to, Hitler was living his days of glory. His success was all the more delectable in that the victory over France was achieved against the recommendations of his generals, who had opposed an offensive in the west.

Obviously something had happened—or not happened—in Hitler's Reich. The blunt truth was that the Nazis had no atomic weapons. This seemed so beyond comprehension that Allied scientists at first suspected an attempt to humbug them. Samuel A. Coudsmit, the senior member of the Alsos intelligence team which landed in Normandy, believed (and continued to believe in the 1970’s) that Carl von Weizsacker, and Nobel laureates Max von Laue and Werner Heisenberg, the three most brilliant German physicists, could have built bombs between them with support from the state. They asked German scientists: what about it?

In those days Germans were blaming Hitler for everything, but in this instance their account was plausible. The Fuehrer's anti-Semitism had driven their most promising colleagues out of the country, the Nazi bureaucracy was indifferent toward long-term research, technical equipment was unavailable, and—a typical example of inept rivalry within the Nazi hierarchy —uncoordinated atomic research was being carried out by the Ministry of Education, the War Office, and even the Post Office Department. The turning point for the Germans had come on June 6, 1942, just as the American scientists were approaching their breakthrough. That Saturday Heisenberg briefed Albert Speer, Hitler's Minister of Supply, on progress in the Reich's uranium research. There was definite proof, he said, that Germany had the technical knowledge to build a uranium pile and acquire atomic energy from it, and theoretically an explosive for atom bombs could be produced from such a source. The next step would be to investigate technical problems—the critical size, for example, and the possibility of a chain reaction. At that point he and von Weizsacker were talking about a pile not only as a weapon in itself but as a prime mover in weapon production. Speer gave them tentative approval. The work would continue, but on a smaller scale, and their target should be a pile usable as a generation of power. Speer was only echoing Hitler. The Fuehrer, certain of imminent triumph, had just ordered the termination of all new weapon projects except those which would be ready for use in the field within six weeks.

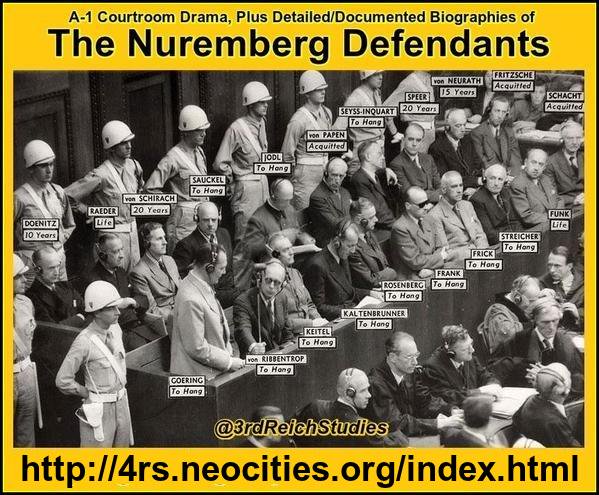

According to Speer— he was convicted at Nuremberg and served twenty years as a war criminal— Hitler had sometimes mentioned to him the possibility of an atomic bomb. Speaking with the Fuehrer on May 6, 1942, Speer raised the question of an all-out program to make one. He suggested that Goering be placed at the head of the Reich Research Council to emphasize its importance, and this was done.

On June 23, 1942, Speer reported to Hitler. The Fuehrer was still interested, but he had no grasp of theoretical physics, and the project was shunted aside. German physicists were now talking to Speer of a three- or four-year project for bomb production. Instead, he recalls, "I authorized the development of an energy-producing uranium motor for propelling machinery. The Navy was interested in that for its submarines.'' Speer leaves no doubt that had he dreamed of the Manhattan Project, he would have moved heaven and earth to catch up with the Americans. He continued to make periodic inquiries, but now Hitler was discouraging him. The Fuehrer's old party cronies were ridiculing America's reputation for efficiency, and he had taken to describing all physics as Jewish physics (judische Physik). But if the German dictator had given his own scientists the blank check Roosevelt had given their colleagues in the United States, the maps of Europe and even of the western hemisphere might have been sharply changed.

LUNCH HOUR: During lunch Keitel was overheard telling Sauckel, Frank and Seyss-Inquart that if somebody had guts enough in 1943 to tell Hitler that the war was lost, they could have saved a great deal. The only man who could have done it was Speer, because he was the one who knew that they could not turn out enough tanks, planes, and ammunition to win the war.

Sauckel was very angry at Speer for having put him in a bad light with respect to slave labor. He complained angrily that Hitler and Speer were always putting through orders to squeeze all the labor they could out of both the Wehrmacht and foreign countries for the war industries. Both Keitel and Sauckel seemed to think that Speer was to blame for everything.

AFTERNOON SESSION: In the afternoon session Speer made his statement of common responsibility, "all the more so since Hitler shirked that responsibility before the world by committing suicide." [Rosenberg looked down the dock at Goering. They exchanged looks as if to say, "Here it comes."] Speer declared that the war was strategically lost in 1943, but he realized that it was actually utterly lost from a production viewpoint in January, 1945, at the latest. Nevertheless, Hitler gave orders to continue fighting and to destroy industrial installations in the occupied territories upon retreat. Speer was able to have these orders circumvented to a large extent. The situation was hopeless, "but Hitler betrayed us all." Rumors of "wonder-weapons" were spread to keep up an unrealistic optimism among the public. Phony diplomatic discussions were mentioned to deceive everybody. General Guderian told Ribbentrop the war was lost, but Ribbentrop came back with orders from Hitler that such defeatist expressions would be treated as treason.

Hitler ordered a press campaign with the slogan "We will never surrender" so that no real peace negotiations could take place. Even in his speech before the Gauleiters in 1944, Hitler had indicated that the German people were not fit to survive if they could not win the war. He blamed the German people for the catastrophe, not himself. He insisted on fighting to victory or total destruction at a time when it was absolutely obvious to everyone that only destruction remained. But this "scorched earth" policy continued to apply even to German territory as the armies retreated. It became clear that if the war was lost, Hitler really wanted the German people to be destroyed with him. In his despair, Speer decided the only way out was to assassinate the Fuehrer. Speer was reluctant to tell the details [Note: In reality, Speer was anxious to "tell the details"; it greatly assisted his case. -Wally], but the court asked to hear it after the recess.

During the recess there was great tension and excitement throughout the dock. Frank expressed his typical violent ambivalence toward the Fuehrer. First he declared to the others that it was obviously necessary to bring out the truth; then he denounced the attempt to assassinate the Fuehrer. Rosenberg said that as long as Speer's attempt didn't succeed, he ought to keep his mouth shut.

Goering exercised a good deal of self-control not to express himself openly.

Speer described his plan to kill Hitler with poison gas to be thrown into the air-intake of his bunker. He said that at this time it was easy to get sensible men who were eager to co-operate with anybody who was willing to take responsibility for trying to stop the war and the insane orders of destruction. But Hitler only insisted on giving wilder orders for destruction. Speer then quoted from his own letter confirming his conversation with Hitler. Hitler had said: "If the war is to be lost the nation will also perish. This fate is inevitable. There is no necessity to take into consideration the basis which the people would need to continue a most primitive existence. On the contrary, it would be wiser to destroy even these things ourselves, because then our people have proved to be the weaker and the future belongs solely to the stronger eastern nation. Besides, those who remain after the battle are only the inferior ones; for the good ones have fallen." . . . .

At the end of the court session there were evidences of a profound reaction both for and against Speer. Schacht declared, with feeling, "That was a masterful defensel That was the position decent Germans were inl"

Funk, half blubbering, added, "Really—one must hang his head in shame."

Goering left the dock without a word. As the others waited their turn to go down to the prison, Rosenberg cursed at this denunciation of the Nazi leadership. "Well, he didn't have the courage to go to Hitler and shoot him, so what is he talking about? It is easy enough to beat your chest about something you tried to do."

EVENING IN JAIL: Speer's Cell: Down in his cell, Speer lay on his cot all fagged out, complaining of a stomach pain. "Well, that was quite a strain, but I got it off my chest.—It was the truth and that is all there is to it. I wouldn't have been so mad at Goering if he had not tried to falsify history by making a heroic legend out of this rotten business. He, especially, has no right to make himself a hero, because he failed so miserably and was such a coward in our hour of crisis."

The severe food shortages and the ensuing health crisis, which resulted from the British blockade, had illuminated yet other episodes in British history. The Irish famine was suddenly relevant, as were the periodic famines in other parts of the Empire. To preside over one such disaster, it seemed to post-First World War Germany, might be regarded as an act of carelessness, to keep presiding over them began to look like 'systematic devilry'. Once Germany's fortunes improved again, in the mid-twenties, the immediacy of these impressions receded. And as friendliness towards Britain grew, they were less and less talked about, in much the same way that one might choose to ignore the unsavory private habits of an otherwise admired friend.

Not so in the case of Hitler: once the irritant of British hostility towards Germany began to diminish by 1923, the British Empire shone ever more brightly in his mind. By coincidence, Hitler's racial views began to clarify during the same period. And it may be noted that the word 'ruthless' also makes its first appearance at about this time. From now on, the instinct to acquire the British Empire had been racial. An ambition for territorial expansion was simply part of the Anglo-Saxon genetic make-up. The genius of the Anglo-Saxons, Hitler thought, lay, however, in the way they had exploited their racial qualities. The British Empire was 'the result of marrying the highest racial quality with the clearest political aims'. And the 'audacity', the 'tenacity' and the essential 'ruthlessness' with which these aims were pursued had in the past been signally lacking in Germany. Even in 1941, with half of Europe enslaved, Hitler felt the Nazis 'still had a lot to learn there'.

If one accepts the idea of a racially determined British ruthlessness to be at heart of Hitler's conception of Britain after about 1923, his bizarre pronouncements over the years do begin to make sense. Much the same goes for his foreign policy with its otherwise puzzling contradictions.

The breach of the Anglo-German naval agreement of 1935, for instance, before the ink on it was properly dry, has long been seen as evidence of his essential duplicity. How else could the illegal naval build-up be squared with the Nazis' ostensible desire for an Anglo-German rapprochement? There is merit in that argument: supping with Hitler did indeed require long spoons. But if, like Hitler, one is convinced of Britain's own ruthlessness, a covert naval build-up would be an effective insurance against later British hostility. Britain, after all, had been allied to Germany—or rather to individual German states—before. This had not stopped her from deserting these allies if British interests favored a renversement des alliances. One of the most prominent victims of such an about-turn had been Hitler's chosen historical alter ego: Frederick the Great. The well-worn phrase of 'perfidious Albion' has recognizable roots in British policy towards the continent of Europe. Hitler's distinctive innovation was to regard past British actions not simply as evidence of Anglo-Saxon duplicity but as essentially Germanic ruthlessness.

If their Intelligence Service informed them of the vast German deployment towards the East, which was now increasing every day, they omitted many needful steps to meet it. Thus they had allowed the whole of the Balkans to be overrun by Germany.

They hated and despised the democracies of the West; but the four countries, Turkey, Rumania, Bulgaria, and Yugoslavia, which were of vital interest to them and their own safety, could all have been combined by the Soviet Government in January with active British aid to form a Balkan front against Hitler. They let them all break into confusion, and all but Turkey were mopped up one by one. War is mainly a catalogue of blunders, but it may be doubted whether any mistake in history has equaled that of which Stalin and the Communist chiefs were guilty when they cast away all possibilities in the Balkans and supinely awaited, or were incapable of realizing, the fearful onslaught which impended upon Russia. We have hitherto rated them as selfish calculators. In this period they were proved simpletons as well. The force, the mass, the bravery and endurance of Mother Russia had still to be thrown into the scales. But so far as strategy, policy, foresight, competence are arbiters, Stalin and his commissars showed themselves at this moment the most completely outwitted bunglers of the Second World War.

Despite the contrast in the summer of 1941 between a Stalin losing his grip and a supremely confident, militant Hitler, the same criticism can be applied to Hitler too. The German army penetrated deep into Russia and inflicted huge losses on the Red Army, but it failed to win a decisive victory before the winter—the blitzkrieg gamble on which Hitler staked everything. As the consequences of the failure unfolded, compounded by Hitler's stubborn refusal to listen to expert advice—as stubborn as Stalin's in the first half of 1941 and again in 1942 —the rashness of such a gamble, and the craziness of his fantasy of exterminating, evicting, or enslaving a hundred million people became more and more apparent. In Hitler's case the power to silence criticism and doubt was fortified as much by the spell of success as by terror. But, in his case as well as Stalin's, it was the system, in which all authority was concentrated in one man, with that one man's limitations, that enabled him to commit a whole nation, without protest, to so reckless an enterprise.

The enterprise could not have been launched without the willing and, in many cases, the enthusiastic cooperation of millions of Germans who share in greater or lesser degree the responsibility for the crimes that were committed. But that still leaves the question whether, if there had been no Hitler, Germany would ever have embarked on an invasion of Russia aimed not just at the defeat of the Russian army or even the destruction of the Russian state, but at the enslavement of the Russian people. There is nothing to suggest that there was any other member of the Nazi leadership or of the wider circle of German nationalist politicians who combined the imagination to conceive so fantastic an undertaking with the sorcerer's ability to persuade so many others with much greater practical experience of soldiering, business, industry, and administration, to engage in the attempt to carry it out.

The argument still heard in Germany that Hitler had no option because of the threat of a Russian attack does not stand up to examination of the evidence. If the answer is that wars are the product of structural, social, and economic tensions, one may ask what tensions and contradictions there were in German society in 1941, as distinct from 1939, which could only be satisfied or diverted by an attack on Russia, when the greater part of the European continent was under German control already and offered virtually unlimited scope to the ambitions, idealism, organizing ability, and greed of Germans of all classes.

There was a moment of silence, until Badoglio decided to be safe and called Mussolini, who answered: "I agree. It's best that they stay where they are."

Pricolo remembered: "We were all very moved: one could not witness the armistice, albeit a moderate one, with a nation like France, defeated practically without a fight. Huntziger said to Badoglio, 'Marshal, in the present, infinitely painful circumstances, the French delegation is comforted by the sincere hope that the peace which will follow shortly will allow France to begin its task of reconstruction and renewal and will create the basis for lasting relations between our two countries in the interest of Europe and of civilization.'

At the end of the meeting, wrote Pricolo, "we all went to see Mussolini, who received us in an angry mood. 'The only thing missing was for you to start crying,' he said sarcastically. Ciano quickly informed him, 'Obviously . . . as I said, we were emotional, but this was justified because since Caesar's conquest of Gaul, it was the very first time that Italy was imposing an armistice on France, the nation of grandeur, the France of the kings, the France of Napoleon.'"

Robert Aron summed up the French delegation's impressions: "The Italians seemed to be excusing themselves for picking up the spoils of someone else's victory. Count Ciano shook hands very cordially with Ambassador Noel. Badoglio had greatly watered down the original text. The occupation of French territory was excluded except those areas already in the hands of Italian troops, a purely formal clause. The article regarding the handing over of Italian political refugees was canceled... Italian control on French territories, namely North Africa and Syria, was reduced to a minimum . . . . At the moment of signing, Badoglio said happily, 'I hope France will have a resurgence; it is a great nation with a great history, and I am certain that it will have a great future. From one soldier to another' he said to Huntziger, 'I sincerely hope so.'