-------------

-------------

Anna Beauchamp (@Zabiegana) Kraków, Poland

----------------------------------

---------------------------------

----------------------------

Son of Sandor (@Son_of_Sandor) May 10, 1945 WWII NYT "Reich High Command's Final Communiqué"

Holocaust Council (@HolocaustGrMW) Holocaust survivors remember at Yom HaShoah service at @jfedgmw in New Jersey - http://bit.ly/1rGVwAy

Efraim Zuroff (@EZuroff) Justice after the Holocaust http://toi.sr/1s3jPbV via @JewishStandard Wise words from a veteran of the fight vs. anti-Semitism

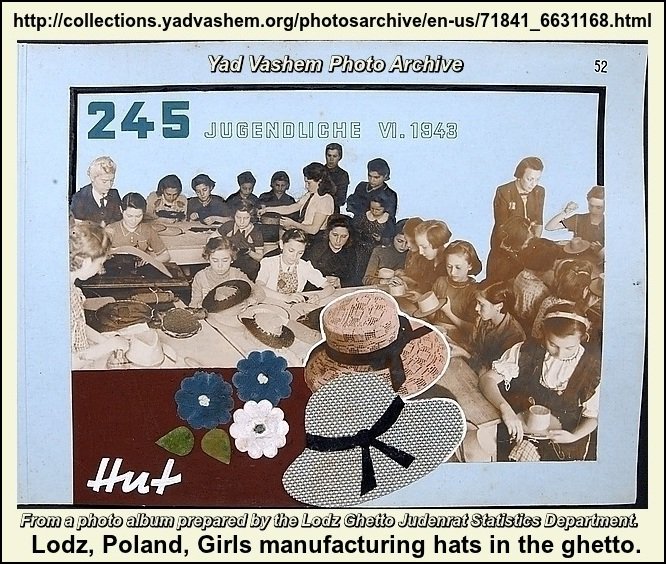

A memorial plaque inside the synagogue. Its title reads: “In memory of the Jews of Hania the community of Etz Hayyim Synagogue, who perished 9 June 1944.”

Efraim Zuroff (@EZuroff) Anti-Semitism is a prejudice different from racism, with which it is confused http://on.wsj.com/1WqBzum

Today’s Comic: James Corden: “Donald Trump is finally sitting down with his nemesis, Speaker of the House Paul Ryan, to discuss unifying the Republican Party after they have been trash-talking each other for months. Ryan is in a difficult spot. On the one hand, Trump has made a lot of offensive statements. On the other hand, Trump is his party's only chance at winning — and because it's Trump, both of those hands are very, very tiny. Paul Ryan right now is like a girl at a bar at the end of the night where all the hot guys have left. So she's trying to convince herself that it would be worth taking home the guy with the orange skin and weird hair. But Ryan is not the only one who seems to be changing his mind about Trump. Former presidential candidate John McCain stated this week that he thinks Donald Trump could be a “capable leader.” John McCain spent several years in a Vietnam prison, and now saying “Donald Trump is capable” sounds like the hardest thing he's ever had to do. I'm sorry, but saying Donald Trump could be a capable leader is not very reassuring. If you are about to have an operation and they tell you that your doctor could be a capable surgeon, you would be like, ‘You know what? It was a minor heart attack. I'm good. Don't worry’.”

Today’s Insults: “Donald Trump is now saying that his proposed ban on Muslims was "just a suggestion." Then he admitted his presidential campaign is "just a bar bet." - Here in California, a white supremacist has resigned from being a Donald Trump delegate. When asked why, the white supremacist said, "Because that guy's crazy." - During the Republican convention in Cleveland, an artist is going to photograph 100 nude women to make a statement. The statement is, "This is the only way to get people to Cleveland." - The FBI just announced yesterday that fewer and fewer Americans are going off to join ISIS. Or as Fox News reported it, "Once Again, Jobs Drop Under Obama." - The producers of the X-Men movies say their next X-Men movie will take place in the 1990s. In it, the X-Men use their superpowers to try and stop the Backstreet Boys. - At this moment, a 7-Eleven cashier from Connecticut is trying to become the first woman to climb Mt. Everest seven times. She said, "If I can survive a 7-Eleven hot dog, I can survive anything." - Google has created several new emojis aimed at empowering women. So congratulations women, you asked for equal pay and you got five new emojis.” –Conan O’Brian

Today’s Wisdom: “I don't want to believe. I want to know.” -Carl Sagan

Twitter: @3rdReichStudies

Note: Images may or may not accurately represent the item adjacent to them. Also, please note that there is much, much, MUCH more detail available-and many, many, MANY more items as well-every day on the linked What Happened Today page. For the full story behind the events of this day, click the May 17 & May 18 & May 19 & May 20 & May 21 & May 22 & May 23 link. Really, May 17 & May 18 & May 19 & May 20 & May 21 & May 22 & May 23. Seriously, the May 17 & May 18 & May 19 & May 20 & May 21 & May 22 & May 23 link is the one to click. That's right, this one: May 17 & May 18 & May 19 & May 20 & May 21 & May 22 & May 23 Disclaimer: The selected Quotes, Jokes and Cartoons may or may not represent the views of the compiler of these daily posts. If they give you something to think about, they will have accomplished their task. Levi Bookin, Copy Editor, in particular bears no responsibility for any of them. He does, however, do a truly admirable job on the linked Daily pages, which everyone should peruse on a daily basis. It is WELL worth the small effort required. The Trick is to Click-> May 17 & May 18 & May 19 & May 20 & May 21 & May 22 & May 23

From Justice At Nuremberg, by Robert E. Conot (***): On the opening day of the war, a German submarine had sunk the British passenger liner Atbenia under the mistaken impression that it was an auxiliary cruiser. About a hundred Americans had been on board, and, because of the resemblance to the Lusitania incident of World War I, a great hue and cry had resulted. The Germans, from the beginning, had denied responsibility. When, however, the U-boat had returned to port on September 27, 1939, its shamefaced commander had admitted that he had torpedoed the ship in error. The situation had contained the potential for such diplomatic dynamite that Hitler had ordered Raeder and Doenitz to suppress all facts. In a schoolboyish forgery, the log of the submarine had been altered to expunge the record of the torpedoing. Compounding the deception, Goebbels, on October 23, had asserted in a brazen and clumsy piece of propaganda: "Churchill sank thc Athenia." Alleging that Churchill had placed a bomb aboard the ship, Goebbels had characterized him as a "criminal" and a "murderer."

Raeder, professing himself a man of probity and integrity, told the court that Goebbels's propaganda ploy had come as a complete surprise to him. He would, he said, have intervened had he known about it beforehand. When Fritzsche later took the stand, Lawrence exhibited an intense interest in the subject. In response to Lawrence, Fritzsche declared that he had kept making inquiries to the navy about the Athenia: "The answer was always the same. No German submarine was near the place of the catastrophe."

"And are you saying that that liaison officer of the navy told you that after the twenty-third of October, 1939?"

"Yes."

"Did he continue to tell you that?"

"Yes."

"That is all," Lawrence concluded. It was evident that Raeder had never attempted to halt Goebbels's outrageous deception. Thus, so far as Lawrence was concerned, Raeder's posture as a man of character was destroyed.

One of the witnesses called by Raeder was Ernst von Weizsacker, formerly state secretary in the Foreign Office. Alfred Seidl, the attorney for Hess and Frank, grasped the opportunity to renew his campaign to embarrass the Russians and, if possible, generate dissension between the Soviets and their western Allies. A slight, diminutive, bespectacled member of the Nazi Party, Seidl was the bete noire of the tribunal. Buzzing about like a persistent gnat, he pursued his goal of demonstrating that either the Conspiracy to Launch Aggressive War had been nonexistent, or else had included the Russians. "Obviously Seidl is trying to cause trouble in the tribunal," Biddle noted.

Seidl's aggressiveness made some of the other German attorneys uncomfortable, and his high-pitched laugh, resembling Frank's, left them uneasy. But he had gained adherents among members of the American prosecution who shared his distaste for the Russians—there was a staunchly anti-Communist group gathered about Father Walsh and Thomas Dodd—and one of them slipped him a copy of the second secret protocol negotiated between the Germans and the Russians following the conclusion of the campaign against Poland. In essence, this added little to the covert addendum to the Moscow Pact which Seidl had already succeeded in introducing; but it gave him one more opportunity to needle the Russians. "Do you know, I have him now, I have him truly," he exulted conspiratorially to Carl Haensel, the assistant attorney for the SS. "There exist two secret protocols. We have the text now. What will they do?"

Rudenko protested: "We are examining the matter of the crimes of the major German war criminals. We are not investigating the foreign policies of other states. Second, the document is—in substance—a forged document and cannot have any probative value."

Rudenko had nothing to back up his claim that the document was forged; and Seidl pointed out that it was the prosecution that had introduced the Moscow Pact as part of its charge of aggressive war. Lawrence maneuvered out of the situation by procrastinating action on the admissibility of the document, but permitting Seidl to question Weizsacker about his knowledge of the treaties, a decision that, in practice, gave Seidl what he wanted.

Though Weizsacker did little more than corroborate what had previously been stated about the division of the eastern spoils, his testimony—added to the revelation of the Soviets' offer of Murmansk as a submarine base to the Germans—demonstrated the extent of Stalin's cooperation with Hitler. The discomfiture of the Russians in Nuremberg was great, and the pending testimony on the Katyn Forest massacre promised to increase it further. A few days after Weizsacker's appearance, N. D. Zorya, one of the assistant Soviet prosecutors, shot himself. (His death was officially described as an accident.)

As each of the defendants concluded his appearance, he lost much of his interest in the proceedings, and the entire front row of the dock and a portion of the second was now encompassed in apathy. Hess had never been present in the courtroom in any form but physical. Ribbentrop, glassy-eyed from his diet of sleeping pills, appeared spectral, as if playing the role of his own ghost. Rosenberg, who seemed to the judges to be constantly writing, was in reality entertaining himself by drawing sketches. Frank, abandoning the trial for euphoric flights into literature and music, floated off into the world of his visions. Funk looked as if, like Humpty Dumpty, he had fallen off a wall and would never be put back together again. Schacht regarded both his fellow prisoners in the dock and the proceedings with disdain. The snap had even gone out of Goering, who, brooding, spent long periods slumped down in his corner as if in a bathtub. The lassitude spread through the courtroom and threatened to become generalized—the seldom-used interpreter sitting behind the American and French judges took to slumbering much of the day, and was left undisturbed until his persistent snoring became an embarrassment to the tribunal.

From The Holocaust: A History of the Jews of Europe During the Second World War, by Martin Gilbert (*****): Inside the Gestapo there were a few Germans who sought to warn the Jews of what was impending. Heinrich Gruber, a Protestant pastor in Berlin, who was later imprisoned for helping Jews, recalled one such German at Gestapo offices in Berlin. The Gestapo always sought to employ those who might have some pathological or personal animus against the Jews. For this reason, they had taken on the father of the murdered German diplomat, Ernst vom Rath. Vom Rath senior was given an official position because, as Gruber later recalled, it was thought 'he would certainly like to get his own back on Jews and would be particularly severe with regard to Jews'. But this, Gruber added, 'was certainly not the case. Our relationship was rather friendly, and I must say that this man helped us clandestinely on many occasions.' Vom Rath senior would, for example, leave out on his desk the latest orders and decrees so that Gruber could see them, and report them to those who might then still have time to take measures to avoid them.

With the Soviet Union still neutral, a number of Polish Jews who had fled eastward in Soviet-occupied Poland and Lithuania were able to escape from Europe altogether, as a result of a curious diplomatic arrangement. In Kovno, the representative of the Dutch firm of Phillips was prepared to issue certificates to the effect that travellers wishing to enter the island of Curacao, in the Dutch West Indies, did not need an entry permit or visa. Armed with this document, Jews persuaded the Japanese Vice-Consul in Kovno, Sempo Sugihara, to issue them a transit visa through Japan, ostensibly to the Dutch West Indies. Travelling to Moscow on this transit visa, the Jews then received permission to leave the Soviet Union through the Far Eastern port of Vladivostok.

Once in Tokyo, many of the Jews went to the Polish Ambassador there — the Ambassador of the Polish government in London — who gave them documents to enable them, as Polish citizens in exile, to travel to Canada. By such stratagems, several thousand Polish Jews reached safety in the summer and autumn of 1940. Among them was Leon Pommers, a twenty-six-year-old music student from Warsaw, who, more than a year after leaving Kovno, having travelled through Japan to Shanghai, Hong Kong and Australia, finally reached San Francisco in February 1942.

In Shanghai were twenty thousand Jews, two thousand refugees from Communist Russia, who had found a haven there before 1933, the majority refugees from Germany, who, since 1933, had been able to take advantage of the fact that, alone of all states or cities, Shanghai since 1933 had not required a prior visa or permit to enable a Jew to live there.

The Japanese government also took in several hundred Jewish refugees who had managed to cross the Soviet Union during this period of Soviet neutrality. One small Jewish community in Japan, that of Kobe, gave the Japanese authorities a guarantee that refugees would not become a financial burden on Japan. Following this guarantee, refugees who landed at the port of Tsuruga from Vladivostok were admitted to Japan without question, welcomed at Tsuruga by members of the Jewish community, and brought to Kobe by train. In this way, 'many hundreds' were housed and cared for, a German Jewish refugee, Kurt Marcus, later recalled. But the task of financing the refugees was beyond the resources of the Kobe Jewish community; they therefore sought, and received, help from the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee. Recalling his nine years as a refugee in Japan, Marcus added: ' At no time did I experience even the slightest hint of anti-Semitism.'

While Nazi terror in Poland tightened its grip, Britain and France, at war with Germany since September 1939, had made no military move against Hitler's Reich. These were the months of the Phoney War. In Warsaw, Chaim Kaplan noted in his diary on 7 March 1940, 'Those who understand the military and political situation well are going about like mourners. There is no ground for hope that the decisive action will come this spring, and lack of a decision means that our terrible distress will last a long time.'

From Bodyguard of Lies: The Extraordinary True Story Behind D-Day, by Anthony Cave Brown(****): Far more successful in aggravating German fear of an invasion of southern France was an operation called "Royal Flush." In a diplomatic maneuver conducted at the express instructions of Brooke, Marshall, Hull and Eden, the American and British ambassadors at Madrid called upon the Spanish Foreign Minister, General don Francisco Gomez Jordana, to request the use of facilities at the port of Barcelona for the evacuation of Allied casualties in "impending operations." At the same time American and British diplomats appeared among the wharfingers of Barcelona, asking questions about the port's capacity to handle food and "other supplies," berthing arrangements and billeting facilities for surgical and nursing personnel.

To all appearances, the Allies wished to turn the "Manchester of Spain" into a hospital for some great campaign shortly to be undertaken on the other side of the Golfe du Lion in southern France, a campaign that was indeed planned but for a later date. Would the Spanish government cooperate? The answer reached the Germans as quickly as it reached the Allies; yes Generalissimo Franco would be pleased to provide suitable space at Barcelona for 2000 hospitalized men and their attendants together with all dock, labor, warehouse and other facilities of the port. When this information was allied to intelligence about the activities of the American 91st Infantry Division, to the rapidly growing size of the French 1st Army in North Africa—an operation that was costing the United States $1.2 billion—and to the incessant prowling of reconnaissance ships and aircraft, OKW decided to keep its entire Army of the Riviera in place for the time being—including its panzer divisions.

Well before the Copperhead charade had run its course, Eisenhower had issued the last of a series of orders that marked the end of the Neptune preparatory period. After a long and careful study of the tides, the phases of the moon, the hours of daylight and the currents, Allied planners had agreed that only three days in early June—the 5th, the 6th and the 7th—filled all the basic requirements of Neptune. "Y-Day," that day when everything must be ready for the assault, was set for the 1st of June, and its code word was "Halcyon." June 5 was selected as the day of the assault, but the 6th and 7th would also be acceptable if bad weather interfered on the 5 th. If the expedition could not sail on any one of these three days for any reason—particularly the weather—the next period during which all the natural factors would combine to favor Neptune would be between the 19th and the 22nd of June.

No one could predict what the weather might be during that first week in June. But with Halcyon set, Eisenhower ordered the great concentration of military force to begin in the counties of Cornwall, Devon, Somerset, Gloucestershire, Wiltshire, Dorset, Sussex and Surrey. On May 18, 1944, convoys—often 100 miles long—started to snake their way down quiet English roads to the embarkation points. Tanks with bridges over their turrets, and arms to lay them across ditches; tanks with trailers and strange nozzles to blast German positions with liquid fire; tanks with great bundles of wood overhead to lay in culverts and permit other tanks to move across; tanks with flails of chains to cut passages through minefields; armored cars, jeeps, ambulances, mobile headquarters, field kitchens, mobile hospitals, weapons carriers, half-tracks, Dodge and Bedford trucks by the thousands; mobile wireless and radar stations, anti-aircraft guns, self-propelled artillery, tank trucks—weapons and vehicles of every shape, every size, for every purpose, and in an abundance never before seen anywhere, advanced into the concentration areas to be loaded into the largest fleet in the history of maritime affairs. Yet such was the miasma of secrecy and deception that there were many who believed—as did Hitler—that the whole affair was mere shadowboxing. Eisenhower's diarist recorded on May 18: "Whitman [of the New York Daily News], a veteran war correspondent . . . told me that some correspondents believe there will not be an invasion, that talk of one is a giant hoax."

As the troops concentrated and tensions mounted, there were many portents and alarms. A Finnish professor announced that a comet would shortly appear over Europe, and Berlin radio urged the German people lo ignore (he old superstition that the phenomenon portended catastrophe. The women of Caddington in the Chiltems swore they saw the Angel of Mons in the night sky, just as it had been seen before the great battles in Flanders in the First World War. They refused to believe it when they were told that the vision was no more than a combination of flares and searchlights being tested to illuminate the ground at night. The world stood still for an hour on the evening of May 27 when a woman announcer on Berlin radio interrupted a program to declare: "Ladies and gentlemen, we have sensational news. Stand by for it later in this program. . . ." But the tension eased when Berlin radio later announced: "And now to the important news. In just a few moments you will hear a very talented Berlin artist play on a violin that was made in 1626."

The fears of ordinary people were magnified by the absence of news, but apprehension was no less great among those who knew all about Neptune. The Supreme Commander told his doctor that he was suffering from an almost intolerable ringing in the ear—a sign of extreme nervous tension. His diarist wrote: "Ike looks worn and tired. The strain is telling on him. He looks older now than at any time since I have been with him." And Eisenhower himself wrote in a letter to his friend General Brehon B. Somervell, in Washington: “. . . tension grows and everybody gets more on edge. This time, because of the stakes involved, the atmosphere is probably more electric than ever before . . . we are not merely risking a tactical defeat; we are putting the whole works on one number. A sense of humor and a great faith, or else a complete lack of imagination, are essential to sanity.”

Napoleon or Wellington might have expressed himself better, but the sense would have been the same.

Only Montgomery seemed quite impervious; like a monk, he worked and prayed in his caravan, venturing forth into the sunlight to speak to his men of the "holy crusade" on which they were about to embark. Other generals were apprehensive. On May 12, 1944, Smith had expressed the view that "our chances of holding the beachhead, particularly after the Germans get their buildup, are only fifty-fifty." Fifty-fifty—and it had taken the entire military, industrial, economic and intellectual resources of the Anglo-Saxon world four years just to mount the expedition.

From Corporal Hitler and the Great War 1914 -1918: The List Regiment, by John F. Williams(****): Attempts to discredit Hitler's war service were not confined to speculation about Iron Crosses or limited promotion, for it was also suggested that Hitler was no proper soldier at all, 'merely' a dispatch runner. While a dispatch runner rarely endured the long-term suffering of day-to-day life in the trenches, it was, as Meyer (himself an infantry company commander) explained, 'frequently the case that company runners had to move under the heaviest enemy fire in open country', running risks largely unknown to ordinary infantrymen. It is a measure of the dangers involved that by the armistice only one of the regimental dispatch runners of 1914—15, Schmidt, was still actively serving. As far as Hitler's military career is concerned, it is unlikely that he could have developed his understanding of tactical cause and effect as a corporal serving four years in the trenches. Yet of all non-commissioned soldiers, a dispatch runner, liaising between headquarters and the men at the Front, is often in a unique position to observe and follow the ebb and flow of battle. This 'poor observer' obviously had a good eye for battlefield dangers and the lay of the land, so good that 'under no circumstances [would] the regimental staff want to lose Adolf Hitler as a company runner'

Wiedemann's string-pulling to prevent Hitler's transfer to a crack Bavarian unit in 1916-17 suggests how much he valued the services of his favorite orderly, but he was not among those who thought Hitler should have been promoted. As he made clear from the dock during one of the Nuremberg trials of 1946-47, Wiedemann felt Hitler lacked many of the qualities expected from a senior NCO or junior subaltern. In response to the question from the chief prosecutor, Professor Kempner, 'You were Adolf Hitler's superior in the war. Can you tell us why he was not promoted beyond corporal?', Wiedemann replied, 'Because we could not discover any outstanding leadership qualities in him'.

'Therefore, because he did not have a leader-personality!' Kempner finished the interrogation amidst the laughter of all present – including the accused . . . How I had answered Kempner was true however. From a military viewpoint Hitler at that time had none of the stuff of a superior officer [his] bearing was careless and his answer, when one asked him something, was anything but militarily brief. Most of the time his head was inclined lop-sidedly towards his left shoulder.

Not all Hitler's peers were that impressed either. In the 1930s, by which time Hitler had already become chancellor and Wiedemann his personal adjutant, the latter met up with Weiss Jackl. The former dispatch runner was now a village mayor in an upper Bavarian hop-growing district. When he [Jackl] asked me: 'Captain sir, did you have any idea at that time, when Hitler was still an orderly with us, that something outstanding would come out of him? I tried to draw myself out of the situation diplomatically - I was still Hitler's adjutant: 'You were clearly much closer to him than I, did you notice something?' 'Nah, he sometimes gave us political lectures', Weiss Jackl answered. 'Sure we would have thought that he might someday become a Bavarian provincial politician, but Reich chancellor - never!'

Since Weiss Jackl had last seen him in the war, Hitler had transformed himself. Wiedemann first became aware of this in the early 1920s. On learning that Hitler was to address a meeting, he asked a former List Regiment officer whether this could be 'our Hitler for he can't speak at all!' 'It's our Hitler', was the reply, 'you wouldn't recognize him. He appears quite elegant, has trimmed his moustache and conducts public meetings. And he always gets the applause of the masses, whenever he wants it!' Shortly afterwards Wiedemann met the new Hitler:

“That he'd become another man in the meantime was apparent at first glance. He wore his moustache in that way which later was caricatured throughout the world [but] displayed a confident manner. The way in which he spoke to me reminded me no more of the earlier, somewhat unmilitary dispatch runner; this was now a man who in between times had made something out of himself and had become more accustomed to giving orders than receiving them.”

The Lucky Linzer's experiences in the Great War and the belief in his own destiny made him a high-stakes political gambler in the 1930s and conditioned the manner in which he, as supreme warlord, would fight the Second World War. Hitler regarded himself as a military genius and was sure that his experiences in the Great War gave him a vital edge over even the most able staff officer. There were some at Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW) who agreed with him. Major General Walter Scherff, a Nazi general who saw himself as the Treitschke of the Third Reich, described Hitler as 'the greatest military commander and head of state of all time [a] leader of armies, a strategist and a man to inspire unshakeable confidence'. At his own trial at Nuremberg in 1946, Field Marshal Keitel remained an unabashed admirer, claiming of Hitler that it was 'impossible to prove any error on his part... I must admit openly that I was the pupil and not the master.' Less besotted generals saw him in a less flattering light. After 1942, Hitler's Great War experiences encouraged him to forbid 'even the temporary evacuation of conquered territory or to weaken secondary fronts and theatres in favor of sectors where a positive decision might possibly have been achieved'.

He persisted 'in the view deriving from his experiences in the Great War that the generals' one idea was to give ground'. A former OKW officer, Johann Graf (Count) Kielmannsegg, offered this assessment of Hitler as supreme commander:

“Hitler was first of all what one would call a military dilettante. He was very much shaped by his experiences in the Great War, in which he was without doubt a brave soldier. Hitler was well aided at times with his knowledge of and rapid memory for a mass of military detail and thus could discuss many military matters. Hitler had ideas, which in an operational respect were in part not all that bad. However, he completely closed his eyes to obstacles, restrictions and problems. He believed that everything could be compensated for through ideology [by] the National Socialist spirit of his troops, which was of course complete nonsense.”

According to Ulrich de Maiziere, another staff officer, the German campaign for the Caucuses and Stalingrad demonstrated 'the greatest weaknesses of Hitler the Commander-in-Chief. 'He lacked any feel for logistics in war. Consequently, his operational aims and his decisions became increasingly unrealistic. They were opposed to reality and demanded so much too much of the troops that negative consequences were unavoidable.' Wiedemann, in summing up the military career of a man he knew better than most, wrote:

“Hitler can only completely be understood when one considers his military development. He was basically, as strange as it sounds, of a soldierly nature. In 1914 he volunteered immediately and loved soldiering, a brave and reliable dispatch runner... He, who previously had led the life of a bohemian, uncertain and disordered, submitted himself without protest to the hard discipline of the soldier's life and even found pleasure in it. Later as Reich chancellor, he spoke gladly and proudly of his memories as a soldier. I never heard of a word of criticism from him about what he had experienced as a simple soldier. He retained this preference for the military life even when he was leader of the Party and the German people. Amman, the former regimental clerk, rightly told me when I saw him again in 1933: 'Hitler is first and foremost a soldier.'

In Wiedemann's view, Hitler had 'considerable military abilities'. Without Hitler's urging 'the motorization of the German Army would not have been so rapid and would not have undertaken so completely'. In ordering the offensive in 1940, Hitler 'better assessed the inner weakness of France than the military'. He thus decided 'to abandon the old Schlieffen Plan, with its insistence of a strong right wing and instead thrust through the middle of the Ardennes'. Hitler was so impressed with a Soviet tank captured in the Spanish Civil War that he urged (unsuccessfully) the design and mass construction of similar machines. Yet with all his insights and intuition, mitigating against his desire to become 'the greatest commander-in-chief of all time', were weaknesses that could not be glossed over:

“Hitler had little understanding of the work of the general staff. During the war of 1914—18 he had always been at the Front [and] had little idea of how a higher command worked. He thus over-valued the frontline soldier and believed that courage alone sufficed to win a war... Furthermore, the general staff was, in Hitler's opinion, reactionary, not merely in political respects, above all on military-technical questions.”

There can be no doubt how his Great War experiences influenced his military conduct and decisions in the subsequent war. Hitler's ambition, however, was not restricted to a place in history as the greatest military commander of all time. He saw himself as a new Alexander or Napoleon; as the creator and first ruler of an empire that would not founder as theirs had done, but would endure for a 1,000 years. This imperial vision was predicated on two interrelated assumptions: Germany's political and military hegemony over Europe (which would include the conquest of Lebensraum in the East) and the elimination of Jews from the European continent. Since either or both of the aims can be found in the pre-1914 writings of Class and Bemhardi (to name just two), how much his Great War experiences altered or added to Hitler's political attitudes and anti-Semitism is in question.

From The Arms of Krupp, by William Manchester(*****): Surprisingly, the most earnest advocate of decency was Fritz Sauckel, the Reich's chief slaver. In captured documents his position is repeatedly disclosed, and it is always explicit and unequivocal. Although Sauckel died on the scaffold, the guilt for the most odious crimes of which he was convicted is shared by men who survived him and flourished in West Germany's postwar Bundesrepublik. His speeches and reports reveal that he begged his superiors, his subordinates, and above all the Schlotbarone to consider what they were doing. A former merchant sailor, he lacked the intellect of a Schacht or Alfried Krupp; on March 9, 1943, Goebbels wrote pessimistically in his diary, "Sauckel is one of the dullest of the dull." Yet the master slaver saw the core of the issue. Sauckel implored the industrialists who received deliveries from him to provide their dependents with medicine, food, and proper quarters, arguing that "Slaves who are underfed, diseased, resentful, despairing, and filled with hate will never yield that maximum of output which they might achieve under normal conditions."

Krupp, unpersuaded, continued to run the sickest slave program in the Reich. Foreign workers in his 81 major factories were habitually underfed and diseased. In consequence they really were resentful, despairing, or filled with hate. Understandably, with that attitude, they never achieved maximum production. But then, Alfried hadn't expected that they would. "Naturally," he declared in an affidavit signed July 3, 1947, "we could not obtain from them the work output of a normal German worker." Naturally: how could subhumans compete with humans? Of course, he did load the dice. As early as March 20, 1942, when German silos were bursting with the largest food surplus in the country's history—owing to the confiscation of harvests in occupied territories—a revealing interoffice memo disclosed that during a diet conference at Raumerstrasse "Mr. Hassel from the Werkschutz, who was present at the time, butted in and said . . . that one was dealing with Bolsheviks and they ought to have beatings substituted for food." The spokesman for this enlightened approach was one of Alfried's most influential lieutenants; he represented Altendorferstrasse's attitude; and it was in 1942 that a team of Wehrmacht officers inspecting POW camps reported, "Edema cases existed only in Krupp camps." Alfried later conceded that he knew at the time that slaves were starving: "The fact that complaints were frequently made on account of insufficient food for the foreign workers . . . [is] well remembered by me." He blamed "technical difficulties" and "the official regulations, which determined the rations in detail." They did indeed.

And they were sensible. As of February 9, 1942, Russians and Poles who had been drafted for forced labor were supposed to be receiving a minimum of 2,156 calories a day. The figure for those engaged in heavy work was 2,615; in very heavy work, 2,909. Yet what was happening at Krupp during those months? On March 14 the supervisor of a tool shop complained that "the food of the Russians working here is so pitifully bad that they are getting weaker and weaker every day. Investigations have shown, for example, that some Russians are not strong enough to tighten a turning part sufficiently, for the lack of physical strength. Conditions are exactly the same at all other places where Russians are employed. If care is not taken to change the feeding arrangements sufficiently so that a normal output may be expected from these men, then their employment, and all the expense connected with it, will have been in vain."

Elsewhere in the Konzern conditions were the same. Four days later one Krupp foreman wrote another foreman, describing a daily visit by Oberlagerfuhrung chefs: "What these men call a day's ration is a complete puzzle to me. The food was a puzzle, too, because they ladled out the thinnest of already watery soup. It was literally water with a handful of turnips, and it looked like dish water. . . . The people have to work for us. Good, but care must be taken to see that they get at least the bare necessities. I have seen a few figures in the camp, and a cold shudder actually ran up and down my spine. I met one there, and he looked as though he'd got barber's rash. . . . If this continues, we shall all be contaminated. It is a pity, when just at this moment the motto is 'increased production.' Something must be done to keep the people capable of production."

Nothing was done. Eight days later the manager of a boiler construction shop reported on the performance of his Russian soldiers and civilians. Six weeks had passed since their arrival and the beginning of fressen, he noted, and they were "in a generally weak physical condition. . . . 10 to 12 of the 32 Russians here are absent daily on account of illness. . . . The reason why the Russians are not capable of production is, in my opinion, that the food which they are given will never give them the strength for working which you hope for. The food one day, for instance, consisted of a watery soup with cabbage leaves and a few pieces of turnip."

This was Krupp's famous "bunker soup" (Bunkersuppe), which contained perhaps 350 calories. Sometimes it was supplemented by a second meal, a wafer-thin piece of bread smeared with jam, but the survivors' most vivid memories of twilight would be of returning from the shops to confinement and standing in line, racked by hunger cramps, holding out tin cups to receive this vile garbage. Die Firma was one of the few firms whose SS contract permitted it to make its own arrangements for feeding slaves, thus cutting its four marks per diem payments to Himmler. I. G. Farben was another, but Farben slaves were given the full ration, with supplementary meals provided for men assigned to heavy duty. Not so Krupp. At Nuremberg, Kruppianer testimony revealed the desperate straits to which prisoners were reduced:

“The warm meal consisted of soup, the cold one of bread with jam or margarine. The so-called "bunker soup" that was served at Krupp was not touched by many German workmen [Die sogenannte Bunkersuppe, die bei Krupp serviert wurde, wurde von manchen deutschen Arbeitern nicht angeriihrt]. After the air raids in October of 1944, however, even this was no longer available. The night shift never received any extra food . . . Krupp received .70 RM for feeding the prisoners per head per diem [Krupp erhielt fiir die Ernahrung der Gefangenen .70 RM pro Tag und Person].”

At mealtimes, as at other times, Krupp tried to maintain the double standard: conscripts from the west were Untermenschen, but prisoners from the east were Unteruntermenschen. To be sure, as the fog of war thickened the distinctions blurred. A Krupp lawyer, cross-examining was told, "Well, so far as I can remember we only got one slice a day." (The slice, he added, weighed about an ounce and a half.) On that diet prisoners deteriorated rapidly, and some of the most poignant stories this writer heard from survivors were of men who returned from Essen to their homes in France and the Low Countries and were ejected—the doors literally slammed in their faces—because their wives and mothers didn't recognize them. In general, however, captives from the east received less of everything except brutality. "Of all the military prisoners they fared the worst," the Nuremberg tribunal concluded, and the judgment is supported by over five hundred pounds of testimony, documents, and exhibits.

The decision to abuse them had been made on the very highest level. In one memorandum the office manager of the firm's locomotive factory recorded that Lehmann, who received his own orders directly from Alfried, had told him that each Russian would receive "300 grams of bread between 0400 and 0500 hours." The manager added, "I pointed out that it was impossible to exist on this bread ration until 1800 hours, whereupon Dr. Lehmann told me that the Russian prisoners of war must not be allowed to get used to western European ways of feeding."

From Nuremberg Diary, by G.M. Gilbert: (***) May 22, 1946 - LUNCH HOUR: At lunch Doenitz was tickled over the statement he had just gotten from Admiral Nimitz in answer to his questionnaire. "Do you know what he said? He conducted unrestricted warfare in the whole Pacific Ocean from the first day after Pearl Harbor!—It is a wonderful document!"

In the next room Ribbentrop and Raeder were also taking great comfort from the document, which Doenitz had shown them. "You see," said Raeder, "unrestricted warfare—anything is permitted as long as you win! The only thing you mustn't do is lose!"

Ribbentrop sought to use this even to justify the breaking of the Munich Pact. "There you are—unrestricted warfare in the whole Pacific Ocean, where America really doesn't belong! And when we make a Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, which belonged to Germany for a thousand years, it is considered aggression!"

"But there is still a difference between the two situations," I pointed out. "You had signed a pact in Munich not to take more than the Sudetenland, while we were attacked without warning in the Pacific in the midst of negotiations. There is a clear difference there between aggression and defense."

Ribbentrop refused to concede the point.

In the Youth lunchroom, Speer was giving von Schirach his last-minute advice on telling the truth in defiance of Goering's hypocritical stand. I caught only the tail-end of it, where von Schirach was agreeing to tie in his explanation with Speer's.

EVENING IN JAIL Doenitz' Cell: I came into Doenitz' cell with a copy of Raeder's Moscow statement. "Look here, Admiral, I don't know if I ought to associate with you any more! Your own superior officer doesn't seem to think much of your character."

Doenitz was taken aback and dropped his guard, excitedly attacking each sentence in the document. "—But look, Captain, everything here is absolutely wrong!—Don't forget, he wrote that as a disillusioned old man in Moscow who had just attempted suicide. This business about Speer and me—. Do you know why he wrote that?—Because he was jealous over our increased U-boat production over his old-fashioned methods!—That's why I said to him this morning, 'Which is a higher number, 44 or 21?' —Well, by improving on the old-fashioned methods, Speer and I produced 44 U-boats a month instead of the measly 21 that he was able to squeeze out . . . This 'Hitler-Boy' business is a damn lie!—I was never called that. Raeder is just a jealous old man who is sore because I not only succeeded him, but actually accomplished more than he did, and finally I became Chief of State, although I was once his subordinate.—That part about my ordering the troops to fight on at the end—I've already explained to you.—It was only to save two million Germans from falling into Russian hands, and for that I had the support of General Eisenhower and General Montgomery.—No, I told my lawyer, Kranzbuhler, not to say a word about this gripe of a pissed-off jealous old man . . . and Raeder is ashamed to death of it himself. He's been trying for weeks to get that document withdrawn, but he didn't say anything about it because he thought he could get away with it. He couldn't get up on the stand and say that he wrote the statement under pressure, because his family is still in Russian hands.

"Well, I have to put up with him in the dock anyway; I don't want the prosecution to see me hitting him over the head. I've got to stand all kinds of people in that dock, like Schacht and Goering, just to mention two opposites.—But you should see the comments written on the margin of the copy of that document which was passed around among us: 'Jealousy'—'Conceit'—'Jealous griping.'—What do you expect me to do with a jealous old fogey like that?"

I said I was satisfied and we laughed it off. He reminded me again how well he was thought of by the American admiral who had sent his aide to tell him through his lawyer that he had the highest regard for him.

From The Nuremberg Trial by Ann and John Tusa(***): One newspaper described his testimony as "wearying the court." Lawrence (President of the Tribunal) intervened several times and threatened to stop the case unless Schirach stuck to the point, but he had difficulty finding a point to stick to . . . . When the judges withdrew at lunch time they held what Biddle called "a stormy discussion . . . I and the Russians think we ought to stop this hogwash." But other judges would not allow an intervention: "De Vabres thinks we must have 'psychological' background. Parker doesn't want the world to get the impression we are stopping freedom of speech." So that afternoon Schirach was left relatively undisturbed to try to persuade his listeners . . . .

Schirach gave testimony for a day and a half. He did not impress his audience. Many people, such as Ossian Goulding, were alienated by the tall, pallid man's "supercilious accents." Most people viewed him with a prejudice which, after the manner of the time, they hid in euphemism. Schirach might behave like the eternal scoutmaster, but he exuded the whiff of the kind of scoutmaster who ends up in the Sunday newspapers. But no one could bring themselves to use the word "homosexual." Instead an interrogator had written of his "rather unpleasant good looks," and the way his "tendency to puffiness seems to have been held in check." Someone else compared him to Ivor Novello, "anxious to keep up his youthful appearance."

Gilbert's report to Andrus was even more circumspect and talked of Schirach as "a curious aesthete with a narcissistic streak." Gilbert had gone on to say that Schirach's early rise to power had gone "to his romantic head" and that he was now "disillusioned at what he feels to be the betrayal of German youth by the elder leaders." Gilbert had actively nurtured this disillusionment in recent months; tried to wean Schirach from his hero worship of Goering; given encouragement to his flickering wish to condemn Hitler's abuse of German youth.

It is hard to believe that Gilbert was acting purely on his own initiative. Others beside must have seen an advantage in persuading the former leader of those young people to reject the training they had received and set them on a less dangerous path for the future. Should German youth come to share Schirach's disillusion, Germany would be easier to settle and incorporate into the European community. But there is no evidence to show that Gilbert discussed his strategy with others. Nor is there a hint anywhere that a bargain was considered. On the contrary, the prosecution records suggest that every effort was made to secure the maximum sentence. Gilberts diary shows Schirach struggling with his conscience, until deciding in early May that he had one last mission to the young people of Germany—to denounce Hitler before he died. He got his courage to the sticking point in the witness box around mid-morning on 24 May. He was noticeably ashen-faced.

Twitter: @3rdReichStudies